Bob Presner is the former President of Film Finances Canada, and former Vice-President of Motion Picture Guarantors. Over a 12-year period he oversaw the successful completion and delivery of hundreds of movies, MOWs and TV series. Today, as President of Beyond the Box, Bob leads creativity workshops that tap into the transferable skills he learned during his 30-year career in the movie business. http://www.beyondthebox.ca/

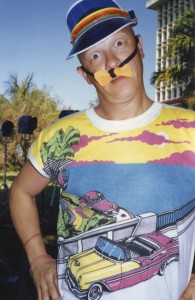

As I settle in for my interview with Bob Presner, former President of Film Finances Canada, he warmly reminds me that it “can’t take too long, because I’ve got 55 people coming in a few hours and we have a little party to plan”. Not surprisingly, his gorgeous Toronto Annex loft can easily handle a 55-person “little” party. We dive right into the conversation of every creative person’s least favourite subject – finances.

Lidia: Let’s talk about Film Finances Canada. I understand they are a ‘completion guarantor’. What does that even mean?

Bob: When an independent filmmaker, not backed by a studio, needs financing to make a movie, the people putting up the money need a guarantee that the picture is going to be completed and delivered. They don’t want to worry about putting up more money if it gets into trouble. The production hires a completion guarantor to provide a bond that basically says to the financiers: “The bond company has the responsibility of completing and delivering the screenplay. In the event that the picture runs into trouble, and if it is at risk for not completing on time and on budget, the bond company will step and do whatever is necessary, including putting up completion sums.”

This gives the bond company draconian powers to do whatever it has to, in order to complete and deliver. And when I say ‘draconian’ I mean, as draconian as removing a director or the producer, or even replacing a star – or even worse, shutting down the movie and paying off the loan. Keep in mind that in 96% of the cases, nothing out of the ordinary happens, because the bond company is monitoring the production on a daily basis to make sure this doesn’t happen. They watch over the film, and if things start to go off the rails, the bond company and their representative will come in and put things back on the rails.

Lidia: It sounds like you’re the kind of both, the “Evil Villain” and the “Hero” of the film world.

Bob: You know that’s a wonderful way of putting it. Smart producers view a bonder as a hero. The really terrific producers that I’ve worked with, and I’ve worked with many over the years, regard the bonder as their ally. They know that it’s possible to get into trouble that they don’t know how to fix. They also know that the bonder has resources beyond their own to solve problems.

Producers who are new to the game know that the bonder has the power to step in at troubled times – and take over bank accounts. They might misguidedly view the bonder as a villain. Nevertheless, as producers get a little more experience, they realize that the bonder doesn’t only have the skill sets to help, but he also can make many assets and resources available to them.

For example, if the first assistant director is not doing their job, and three days into shooting the producer is a full day behind, the producer may decide to have the AD replaced. The bond company is going to have a qualified person standing by to jump in. And that goes for every key position in the show.

Lidia: Looking at these unfortunate scenarios, I guess the films that were finished with the help of a bond company wouldn’t be publicized.

Bob: Well, here’s the thing, the names of certain films that have been bonded are very publically known. It’s not something that gets hidden. Bonders, though because of their unique position, have the ear and the trust of banks, distributors, and government funding organizations. It’s like being a priest – the Holy Father in the confession booth. You’re hearing misery from all sides – and the players are coming to you for direction. A bonder cannot share those confidences and miseries. There are a number of films that have very publicly gotten into trouble. The most famous was Terry Gilliam’s movie: The Adventures of Baron Munchausen. Film Finances in Los Angeles were involved in the costly completion and delivery of that film. And there was even a book written about the whole process.

Lidia: How did you get into this very unique position in the industry?

Bob: Well, I started by spending 18 years practicing my craft. Early on, I was involved in making something like 600 television commercials. I was the head of production for a company that was shooting 100 days a year. That’s 100 commercials a year. Commercials are very imaginative and they ask you to do a lot of different things and solve many problems. These were the days before CGI when they said: “Ok, you have 5 full-size cars come out of the mouth of a giant Tide detergent box.” I had to build a Tide detergent box with all the art work painted on it that was 18 ft. long by 12 ft. high and 8 ft. wide. It had a flap on a hinge that lifted up and five full-size cars literally drove out of the box. Today we would that in seconds through a CGI effect.

I worked on what they called them in those day, “industrials” – the corporate videos of today. Then I started doing feature films as a location manager, a 1st assistant director, a production manager – and then I became a line producer.

Someone described a line producer as the person who answers the call when a producer arrives with a wheelbarrow full of money, dumps it at their feet and says: “Make my movie. I don’t really want to be on the set too much – so when the movie is over, make sure I have enough money to finish post-production. Thank you very much and I’ll see you in five months.” Well, that may be a slight exaggeration, but that’s how it felt at times… I was that guy! I did that on feature films, made-for-TV movies and television series.

So, I had a good 18 years of practice in solving problems of every shape and size. I knew how to get it done – and how to manage people, expectations and egos.

At that point, a bond company called Motion Picture Guarantors scouted me. A very famous guy in the Canadian broadcasting industry, Doug Leiterman, who started a television show called This Hour has Seven Days, asked me to be a risk manager. I said: “I’m sure I can look at projects and determine whether the money available is sufficient to complete and deliver the script. And I know enough about the business to know how to put out fires if they start.” I was VP of Risk Management for six years and then, as MPG was winding down, I was scouted by Film Finances Canada and soon became the president.

Lidia: So how does the guarantor monitor the film?

Bob: Before I talk about ‘taking out a key player’, you should know about the monitoring process. First off, the bond company receives a Production Report and a Call Sheet on a daily basis. The bond company compares the two documents. The production report says something like: They were scheduled to shoot three pages and they only completed 2 4/8th pages – and the 4/8th pages they missed were part of a bigger scene with a very big setup. This means that they’re going to have to go back to that same location and complete the scene, or figure out another way to make up what was not completed. Both potentially costly options. And the weekly Cost Report shows outs the sins…

So on a daily basis you’re tracking what still needs to be done, and what has to be added to the schedule. Every time something has to be added to the schedule, it’s going to cost more money and take more time. In that situation, a smart production manager will say: “Bob, I just want to let you know that I don’t think we’re going to get Scene 41, but we figured if we put a telephone booth in the truck and when we get to Day 13, we drop the telephone booth on that corner, we can just do it as a pick-up because we’re on an exterior on that bridge”. I would say, well and good, that’s fabulous! They solved their own problem. The smart production managers keep the bonder informed as they go.

Lidia: Going back to the scenario on production, what does it look like when that completion guarantor steps in and possibly takes out a key player? How does this even happen? What’s a bad scenario?

Bob: The bonder wants to be there before things get out of hand. So what is out of hand? Say you’re looking at a Production Report and a Cost Report, and you see that there is $46,000 out of petty cash that hasn’t been accounted for – and it’s been sitting on the books for a week. And there are no receipts to cover the advance. And this was an actual case where we found out that the PC had paid for activities that were not directly related to making the film. So the person responsible for the activity was taken out of the financial chain-of-command.

Another example: A lead was involved in some gunplay, not on the set, but off site. That put the film in jeopardy. The producers got the actor out on bail. Together, we had to finish the picture hand-in-hand, because there was a tremendous amount of risk for having someone on the set who was a potential felon.

Then there was the time that the star, speaking calmly about the director (who had done something egregious in a public way on the set) said to me: “Tomorrow, one of us is going to be here, him or me: you choose”. The decision was made to go with the star because what the director had done was so completely off base that there was no other way to go. The producer relieved the director of his duties and we found another director to come in and take over. That shut down the film for three days, but we got the picture back on schedule and delivered it on budget and on time.

Another bad scenario could be that the bonder looks at the cost report and sees severe variances – like the scene with six people in the club was actually shot with 46 people. That means there are 46 ‘extras’ that got paid for an 8-hour call – and that’s many thousands of dollars – and it wasn’t budgeted for. The not-so-smart production managers say “Oh yeah, the director wanted more people”. That’s when you know trouble has arrived. The smart production manager calls up the bonder and says: “The director has added 40 people to the scene. I’ve reduced three other large scenes by 12 extras each. So we’re really only four ‘extras’ over. I’m taking it from the Contingency Fund.” Good production management!

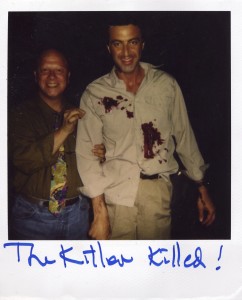

So those are some of the horror stories, but for the most part it’s been wonderful. Over a twelve-year bonding career, to have had only a few situations of high drama and great risk is not bad, considering that over that period I was responsible for overseeing more than 500 different projects.

Lidia: What were some of your favourite moments?

Bob: I went to Winnipeg to check on a film called The Arrow, a wonderful 2-part TV-miniseries with a terrific cast and a great creative crew. One Saturday night, the producer was having a cast and crew party and I asked me to bring my guitar. As I was wailing away, drinking beer and having a good old time – I heard some guy playing the harmonica: just the greatest blues harp I’d ever heard. I turned around and it was Dan Aykroyd. So I looked at Dan and he looked at me – and we just keep playing – and kept on having a good old time. That moment stands out.

I also bonded a picture with Russell Crowe twenty years ago called: For The Moment. It won all sorts of Awards and was Russell’s first North American film. He was a consummate pro and delivered a staggering performance. It’s a beautiful movie, but it was not without trying moments for which my production experience came into play.

Early in the schedule, the production manager called me: “I’m short on the insurance for these World War Two vintage planes that we’re flying and they’ve asked for $86,000 in premiums – and I only have $5,000 in my budget for airplane insurance”. I was able to call an insurance rep that I’d used for years and told him of the coverage woes. In less than 10 minutes we found a work-around that saved the production $78,000 in premiums.

So that was the kind of thing I was more likely to be doing, rather than the heavy drama stuff.

Lidia: It seems like you’ve had all kinds of experiences with producers. Both as the person looking up to the producer for leadership and as person looking over the producer – let’s just talk about some of the qualities of a good producer.

Bob: So the qualities of a good producer: grit; honesty; the ability to think on your feet; emotional intelligence of the highest degree; the ability to handle all sorts of egos. And the biggest task of a producer? Making decisions. Producers who feel they have something to prove are more likely to get themselves into trouble. Producers, who are secure enough to know they’ve chosen the right people, are usually the ones who succeed. For every decision a producer has to make, they have to assimilate all the input about that particular situation and throw out everything except the essentials. And then they have to go with their gut. In the end, resilience is truly the most important quality for anyone in the film and television industry. We used to say: “The difficult we will do now; the impossible takes a few minutes longer.” That takes resilience!